|

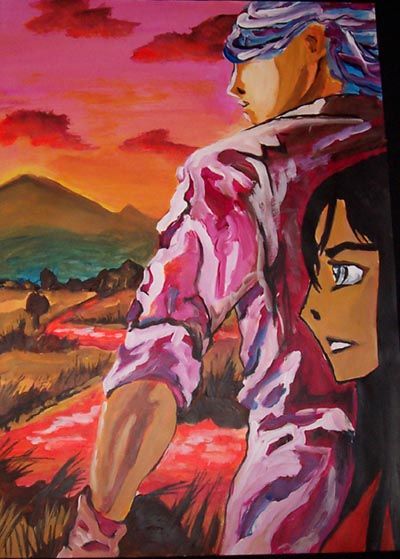

Not alone..

2005.05.23. 04:25

Manga style.. Manga style..

Acryl on paper

And some other manga-related sketches of mine

Here are some of my other sketches, my favorites expl. Alita, Final Fantasy, Tomb Raider...

A History of Manga

The Early Days: Pre-Manga History

The history of manga is one that extends far beyond the birth of anime. Before there was any hint that animation could exist in Japan, people were being entertained by the pictoral art that was manga. Manga, even at its earliest closest form to today's manga, was not much more than comic strips. But even then, its entertainment value was high. The importance and significance of manga is such that it holds a place in the history of Japanese art in general. Manga is no doubt the major source for many of the anime fans enjoy today. How it got to be that way is an interesting and complex story, and this class is designed to help you learn all about it. Let's start by taking a look at the earliest days, the "genesis" of the art of manga.

The term "manga" is itself a word that was not a part of the earliest Japanese words. In fact, the term was coined well after the first examples of what could be called "manga". In the 6th and 7th centuries, monks used to create scrolls which acted as calendars to keep track of time. These scrolls would consist of symbolic icons to represent time, and be decorated with pictures of animals such as foxes, raccoons, and the like, all acting as if they were humans. This was partly done as a form of satire, as the pictures sometimes told stories, but these were the first known "pictoral art" that could be called manga.

But it wasn't until the 17th and 18th centuries that the actual word "manga" was used to describe this form of art. The term was coined by an artist named Hokusai (not his real name), a person who had a very different philosophy on the art and woodblock portrayals that were typical of the time. A man with a somewhat rebellious nature, Hokusai was known to talk back to his teachers and continually challenge their methods of doing things. He would eventually do his own art, and it is thought that around 30,000 art pieces, some of which are grouped into collections and books, survive him. Hokusai did many different pieces, influenced by things such as the art and artistic philosophies of the French and the Dutch, but none seemed to be like his unique style which he called "manga". But it wasn't until the 17th and 18th centuries that the actual word "manga" was used to describe this form of art. The term was coined by an artist named Hokusai (not his real name), a person who had a very different philosophy on the art and woodblock portrayals that were typical of the time. A man with a somewhat rebellious nature, Hokusai was known to talk back to his teachers and continually challenge their methods of doing things. He would eventually do his own art, and it is thought that around 30,000 art pieces, some of which are grouped into collections and books, survive him. Hokusai did many different pieces, influenced by things such as the art and artistic philosophies of the French and the Dutch, but none seemed to be like his unique style which he called "manga".

For Hokusai, "manga" was not the art of drawing characters in a story or paying attention to minute detail in order to create entertaining and meaningful art pieces. Rather, Hokusai's use of the term "manga" (which literally means "whimsical pictures") referred to his method of drawing a picture according to the way his brush or drawing materials glided across the page at random (hence the "whimsical" side of the term). While these turned out to be mostly landscape pictures, the Japanese recognized the free-flowing, yet detailed nature of the art that Hokusai drew, something which was unlike any other art that came before it, in which artists conceptualized what they wanted to draw before they drew it. Hokusai's free approach, though he might not have intended it to be so, may have been the basis for manga artists' diversity, in not sticking to one format but drawing many different kinds of characters and stories. We see that even the earliest "manga" artist was very open about the kinds of things he wanted to depict. And though Hokusai did make a small breakthrough with this art style (one of many kinds of ways he made his art), it wasn't until the early 20th century that some of the earliest "manga" stories began to be told.

The Birth of Manga

By the 20th century, Japan's doors were open to other countries, especially the West, where different cultures and way of life were intriguing to some Japanese people. America, especially, was enjoying a rise to an economical boom and profit. In the midst of all this success came more new and innovative inventions and forms of entertainment. One of these, the "comic strip", would serve to change not only the American and Western cultures, but also that of the Japanese, serving as the catalyst to one of the most dominant parts of the Japanese publishing market today.

Joseph Pulitzer, the publishing pioneer who made the New York World newspaper a resounding success in the early 20th century, was responsible for allowing the first humorous "comic strips" to appear in publication. Consisting of either sequential panels or single illustrations that told a story or made comedic points, the comic strip/cartoon was (and still is today) a source of entertaining diversion from the seriousness of the news and headlines. While the concept of caricatures and cartoons was around in the West long before this, this was probably the first time that regular attention was given to it. Comics such as "The Yellow Kid" (pictured at left) became more and more prominent as newspapers became larger and more important to the American people. Because it was such a success, newspapers and their owners were, even back in these times, willing to go to court to decide ownership of certain strips and features. Joseph Pulitzer, the publishing pioneer who made the New York World newspaper a resounding success in the early 20th century, was responsible for allowing the first humorous "comic strips" to appear in publication. Consisting of either sequential panels or single illustrations that told a story or made comedic points, the comic strip/cartoon was (and still is today) a source of entertaining diversion from the seriousness of the news and headlines. While the concept of caricatures and cartoons was around in the West long before this, this was probably the first time that regular attention was given to it. Comics such as "The Yellow Kid" (pictured at left) became more and more prominent as newspapers became larger and more important to the American people. Because it was such a success, newspapers and their owners were, even back in these times, willing to go to court to decide ownership of certain strips and features.

The Japanese picked up on the comic trend, and a few people back on Eastern cultural shores began drawing their own comic strips and caricatures. One of these was Ippei Okamoto, an artist. Heavily influenced by the work that was featured in Pulitzer's magazine, Okamoto began his own caricatures and comic strips. As with many things that begin with outside influence, Okamoto's and others' first works were very much like the ones seen in the West. The only difference may have been in the reading. Even then, manga strips were read right to left, rather than left to right as the Western comic strips were drawn. This was a minor difference, though in translating Western strips it did make it seem as if the characters were being held up to a mirror, reversing the action of the panels. While the comic strip did take a little while to catch on in Japan, it was, like early Japanese animation influenced by Disney, a beginning that would have far-reaching consequences later on as it boomed into popularity.

By the war, Japanese comics and the caricurists who drew them served many purposes. They were used for humor and comedy, as the Western comics were, but they also were used during the war effort as part of the propaganda and satire used for the benefit of the country and its soldiers. However, with the crushing defeat at the hands of the Allies at the end of World War, many of Japan's cartoonists were censored by the victors, and the progress of what would become Japanese "manga" seemed to be halted. However, after the war, one man would stand at the helm and deliver to the culture, and to the world, Japanese comics as they had never been seen before. This man, Osamu Tezuka, would help to shape the very first modern manga, and begin an industry that still holds significance today in the Japanese culture.

Tezuka's Vision: Manga Takes Form

During and after the Second World War, there was a man by the name of Osamu Tezuka. A factory worker during the war and an aspiring doctor, Tezuka was heavily influenced by the early animation of Disney and the Flesicher Brothers in the West. As a child, Tezuka found solace and enjoyment in his father's projector reels featuring characters such as Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck. He also found popularity and respect among his peers for imitating the style of the cartoons he saw, by drawing ones of his own. It was this early love of animation that would fuel not only his future success, but also, ultimately, the birth of anime and manga as we know it today. During and after the Second World War, there was a man by the name of Osamu Tezuka. A factory worker during the war and an aspiring doctor, Tezuka was heavily influenced by the early animation of Disney and the Flesicher Brothers in the West. As a child, Tezuka found solace and enjoyment in his father's projector reels featuring characters such as Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck. He also found popularity and respect among his peers for imitating the style of the cartoons he saw, by drawing ones of his own. It was this early love of animation that would fuel not only his future success, but also, ultimately, the birth of anime and manga as we know it today.

Historians and knowledgeable fans alike agree that Tezuka was the precursor to both manga and anime, and there's definitely good reasoning and evidence behind it. In the manga field, he was the first to come out with a novel-length drawn story (titled "Shintakarajima", or "New Treasure Island") in 1947, the very first well-known "tankoubon" or "graphic novel" as the West calls them. This graphic novel was about 200 pages in length, which was alone something that had never been seen before. Even more amazing were the images that were drawn by the young artist. Fusing together techniques used in early cinema and the exaggerated cartoon style of the West that was being imitated by Japanese artists, Tezuka created a story that captured the attention of many Japanese readers, both of comics and of books.

Part of the appeal of Tezuka's graphic novel were the intricately drawn scenes and techniques only seen in the monocolor films of the time (which may be a reason for its lack of color - Tezuka was trying hard to imitate cinematic techniques and sights, and all films were in black and white at the time). Using zooming, scene "panning", and stills/close-ups of characters, Tezuka created comics as they had never been seen before. He went on to explain that he felt existing comics in Japan were very limiting and restricted the readers from truly enjoying the experience of reading comics. The novelty and innovation of Tezuka's new technique of drawing comics proved him right, landing at least 400,000 sales in its first publication, an incredible amount for a mostly unpublicized work. Tezuka had begun an comic artist's revolution.

Tezuka went on to draw not only many more famous manga stories, but also many kinds of them. He drew dramatic, action-filled, adult-oriented - the list goes on and on. By drawing many different kinds of stories, and later animating them through his fledgling animation studio, Tezuka was also laying the groundwork for the diversity that manga and anime enjoys to this day. Tezuka's stories were the earliest examples of genres such as shounen (boys manga), shoujo (girls manga) and more. And as Tezuka's success became apparent, many other artists would take this framework for manga and add to it, expanding it to proportions almost undreamed of. Long after Tezuka's first story, manga would, with the help of many artists, become a staple of publishing in Japan. We'll be taking a look at some of the significant events and people of this "popularization" of the manga industry next, as it evolved from the late 20th century to today.

Evolution: Manga's Popularization

By the time Osamu Tezuka and his fellow artists and animators had become established, manga had evolved to a point far beyond that which was seen in the West. The deep story-like elements of Tezuka's manga changed the manga that followed it into not just graphic novels with a plot, but also graphic novels with diverse combinations of story type. Initially, manga audiences ranged in the pre-teens to late teens. This was because much of the early manga produced, by Tezuka and others was either of the shounen (young boys) or shoujo (young girls) genre. The 50's and 60's saw most manga leaning towards one of these two story types. However, as young Japanese manga readers began to get older and lose interest in the stories of shounen/shoujo manga, some manga artists, new and old, began to adapt and draw stories that would appeal to the older audience, in order to keep their interest. It was this almost evolutionary response to its own limited existence that enabled manga to break through as a popular pasttime in the entertainment culture of the East.

Perhaps one of the best known manga artists to adjust and push the age limit on manga readership is Go Nagai. Having formally entered the growing manga industry at the young age of 20 as an assistant, Nagai's works were typically controversial, violent, and racy. Nagai's most famous work was Devilman (pictured at right), which he first released in 1972. Devilman's hero was unlike any hero seen before in manga. They used a combination of the purity of their soul and combined it with that of a demon in order to fight other demons. This somewhat anti-heroic model, along with the violent story, drew criticism from many fronts due to its age-inappropriateness. However, Nagai perservered, having drawn into his fold many older fans who had read shounen or shoujo anime as children. These people were intrigued by the maturity of Nagai's manga, and Devilman, along with many of his future works (such as the notoriously sexy series Cutey Honey) became among some of the most revered in th emanga community, and also some of the first manga series of its target age group to become animated. Perhaps one of the best known manga artists to adjust and push the age limit on manga readership is Go Nagai. Having formally entered the growing manga industry at the young age of 20 as an assistant, Nagai's works were typically controversial, violent, and racy. Nagai's most famous work was Devilman (pictured at right), which he first released in 1972. Devilman's hero was unlike any hero seen before in manga. They used a combination of the purity of their soul and combined it with that of a demon in order to fight other demons. This somewhat anti-heroic model, along with the violent story, drew criticism from many fronts due to its age-inappropriateness. However, Nagai perservered, having drawn into his fold many older fans who had read shounen or shoujo anime as children. These people were intrigued by the maturity of Nagai's manga, and Devilman, along with many of his future works (such as the notoriously sexy series Cutey Honey) became among some of the most revered in th emanga community, and also some of the first manga series of its target age group to become animated.

Another pioneer in the expansion and evolution of manga content and age groups was Hayao Miyazaki. Miyazaki first released works in the 60's, and some of his early work was not unlike the early work of many manga artists who did children's or young boys/girls manga (his first publication was a manga of the famouse "Puss in Boots" tale). However, Miyazaki picked up on the reasons behind the older audience of potential fans, and in the 80's began a project that would take up 13 years of his life, but which would turn out to be his most famous and celebrated work, named "Nausicaa and the Valley of the Wind". With its struggling heroine, poignant depictions of a war-torn, desolate world, and deep themes of ecology and nature, Nausicaa won over many fans over the years that Miyazaki drew it, and the theme of nature vs. man would return in the 1997 film "Mononoke Hime", or "Princess Mononoke", which would be released in Western theatres at the end of the 20th century.

Last but not least, there is world-renown and acclaimed manga artist Rumiko Takahashi. Takahashi's tireless work consists of many kinds of manga (some of which was serialized in weekly publications like Shounen Sunday) and her many successes both in Japan and outside of it show her considerable contribution to the evolution of manga and the increase of its popularity. Takahashi first got fame with her shounen series Urusei Yatsura, about a slightly perverted teenage boy and the alien girl that loves him, but she has written in all sorts of manga story types, from romance (Maison Ikkoku) to horror (Mermaid's Scar), to comedy (Ranma 1/2, pictured at left), to a combination of all three (Inu-Yasha). In all her work, Takahashi has enjoyed much success, and has become one of the richest women in Japan - but even more important than her financial gain was her many-faceted contributions to a manga industry that was growing by the year. Last but not least, there is world-renown and acclaimed manga artist Rumiko Takahashi. Takahashi's tireless work consists of many kinds of manga (some of which was serialized in weekly publications like Shounen Sunday) and her many successes both in Japan and outside of it show her considerable contribution to the evolution of manga and the increase of its popularity. Takahashi first got fame with her shounen series Urusei Yatsura, about a slightly perverted teenage boy and the alien girl that loves him, but she has written in all sorts of manga story types, from romance (Maison Ikkoku) to horror (Mermaid's Scar), to comedy (Ranma 1/2, pictured at left), to a combination of all three (Inu-Yasha). In all her work, Takahashi has enjoyed much success, and has become one of the richest women in Japan - but even more important than her financial gain was her many-faceted contributions to a manga industry that was growing by the year.

All of these figures and many more too numerous to mention here served to promote the new "diverse" manga and its benefits. By the time the late 20th century came around, manga owned a huge chunk of the publishing pie year after year, averaging a percentage of over 40 percent of the publications in Japan. What began as simple random pictures had now become a staple, a career, and an internationally appreciated art form. Let's now close our little history lesson with a look at where manga is today and where it could be going in the near future.

Manga Today: Where it is, Where it's Going

So now you've learned all about the history of manga - its background, its origins, and its evolution into one of the most read publications in Japan. You know about the roots of manga, stretching all the way back through the centuries, and its humble beginnings as an imitation of the Western comic strip. You also know about how one man and his contemporaries morphed manga into a unique and successful industry. We're now going to take a brief look at where the manga industry is today and where it could go in the future.

Today, manga is one of the biggest publication industries in Japan. Tezuka's first graphic novel, referred to as "tankoubon" on Eastern shores, inspired many other manga works and stories which stretch out over many volumes the size of Tezuka's first story, New Treasure Island. Regular publications of manga artists' work are common, and magazines such as Shounen Sunday contain at least 200-400 pages of manga an issue. Manga artists, who work mostly individually or in small groups under no "official" company banner, are numerous, and those who aren't as well known draw for any publication they can get their work showcased in. Some even publish their own work - fans who aren't necessarily known as professional manga artists draw their own manga or draw their own versions of popular manga, termed doujinshi, and these works are also numerous. All of this shows the appeal and respect that the manga industry continues to get, especially in the anime movement, where countless popular manga are converted into anime for the benefit of the fans. Manga's large share of the publication pie in Japan is very much justified. Today, manga is one of the biggest publication industries in Japan. Tezuka's first graphic novel, referred to as "tankoubon" on Eastern shores, inspired many other manga works and stories which stretch out over many volumes the size of Tezuka's first story, New Treasure Island. Regular publications of manga artists' work are common, and magazines such as Shounen Sunday contain at least 200-400 pages of manga an issue. Manga artists, who work mostly individually or in small groups under no "official" company banner, are numerous, and those who aren't as well known draw for any publication they can get their work showcased in. Some even publish their own work - fans who aren't necessarily known as professional manga artists draw their own manga or draw their own versions of popular manga, termed doujinshi, and these works are also numerous. All of this shows the appeal and respect that the manga industry continues to get, especially in the anime movement, where countless popular manga are converted into anime for the benefit of the fans. Manga's large share of the publication pie in Japan is very much justified.

In the West, manga enjoys some success with readers as well. Though the Western comic book industry commands much of the publication sales, manga has nevertheless achieved a following side-by-side with its Western counterpart. The black and white pictures of manga appeal to many people, and many anime fans, including myself, point to their roots in comic books and Japanese manga as their introduction into the world of anime. Some anime fans even have said that they enjoy the manga versions of their favorite anime more than the animated versions. This speaks a lot to the depth of manga, and its ability to draw readers in with its detailed art and story.

Manga continues to flourish in Japan, and other cultures' continue to show their appreciation for it, by collecting their favorite series translated. With a large artist base, a chunk of the publication percentage, and its storytelling and detailed style, manga is definitely here to stay for quite a while. Whether it is through children's stories or adult-only themes, manga has, and will continue to tell stories through its deep and appealing pictures.

source: AnimeInfo

マンガから日本が見える

時代を超えて読み継がれる歴史マンガ

文●米沢嘉博

日本のマンガの最大の特日本の歴史はもちろん、中国やヨーロッパ諸国の歴史まで、歴史マンガが取り上げる時代やテーマは多種多様。根強い人気を誇っているすでに 100巻を超えたマンガも多い。これら大長編作品の中で根強い人気を持ち、世代を超えて読み継がれているのが歴史マンガだ。古代から現代までの日本史を描いた『マンガ日本の歴史』全55巻(石ノ森章太郎)は1万ページを超える大作で、学校の図書館にも置かれている。

歴史マンガでよく描かれるのは、日本人に人気のある戦国時代と、多くの英雄が登場した幕末・維新の時代だ。織田信長、豊臣秀吉、徳川家康などの武将たちが割拠した戦国時代は、池上遼一、本宮ひろし、横山光輝など一流作家たちの多くが描いている。この時代を民衆の側から描いたのが、マンガの古典と言われる『忍者武芸帖』(白土三平)である。

最近の調査で、日本人に一番人気のある歴史上の人物としてあげられたのが幕末の坂本龍馬だ。倒幕勢力を統合させた功績と、自ら自由貿易を進めた豪快で開放的な性格、そして悲劇的な最期を遂げたことが、日本人の心をとらえるのだろう。代表的なマンガノ『おーい竜馬』(武田鉄也・小山ゆう)がある。また、彼ら維新の志士たちに抵抗した勢力である新撰組を扱ったマンガも多い。手塚治虫、水木しげるなどの巨匠が取り組んだほか、最近では大人マンガの描き手である黒鉄ヒロシの『新撰組』もロングセラーになっている。戦国時代と明治維新の時代は、少女マンガからギャグマンガまで、さらにはテレビ、映画、小説とあらゆるジャンルで繰り返し描かれているのだ。

日本の歴史だけでなく、世界の歴史も扱われる。少女マンガの代表作と言われる池田理代子の『ベルサイユのばら』はフランス革命を描いた大長編。中国史物では『三国志』『水滸伝』『史記』などをマンガ化した横山光輝の作品がよく知られている。藤子不二雄(A)の『毛沢東』、安彦良和の『皇帝ネロ』、水木しげる『ヒットラー』などユニークな作品も多いし、手塚治虫の『アドルフに告ぐ』は第2次世界大戦を背景にした歴史ミステリーである。また、細川知栄子の『王家の紋章』は、古代エジプトに繰り広げられるロマンを描いた大長編作品だ。

歴史マンガは時代を超えて読み継がれているが、そのうちの何本かは海外でも出版され、多くの読者をつかんでいるようだ。歴史の壮大なドラマは時代や国を問わず、人々の心をとらえるのだろう。

|